[email protected]

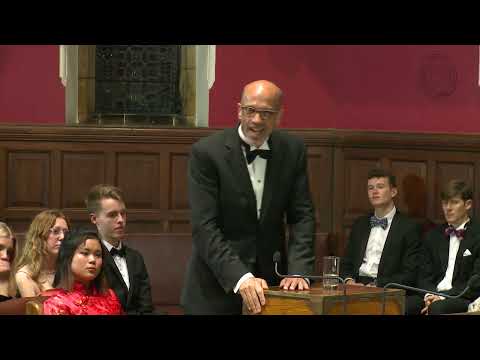

Daniel Markovits

Guido Calabresi Professor of Law at Yale Law School; Author of "The Meritocracy Trap"; Founding Director, Center for the Study of Private Law

Daniel Markovits is the Guido Calabresi Professor of Law at Yale Law School and the Founding Director of the Center for the Study of Private Law. Markovits publishes widely and in a range of disciplines, including law, philosophy, and economics. His writings have appeared in Science, The American Economic Review, The Yale Law Journal, PNAS, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time, and The Atlantic. In 2021, Prospect Magazine named him to its list of the world’s top 50 thinkers.

His current book, "The Meritocracy Trap" (Penguin Press, 2019), develops a sustained attack on American meritocracy. The book places meritocracy at the center of rising economic inequality and social and political dysfunction. The book takes up the law, economics, and politics of human capital to identify the mechanisms through which meritocracy breeds inequality and to expose the burdens that meritocratic inequality imposes on all who fall within meritocracy’s orbit.

Markovits is also working on a new book, tentatively called "The Good Life after the Age of Growth."

After earning a B.A. in Mathematics, summa cum laude from Yale University, Markovits received a British Marshall Scholarship to study in England, where he was awarded an M.Sc. in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics from the L.S.E. and a B.Phil. and D.Phil. in Philosophy from the University of Oxford. Markovits then returned to Yale to study law and, after clerking for the Honorable Guido Calabresi, joined the faculty at Yale.

An illuminating speaker, Markovits explores themes of inequality, opportunity, and democracy for audiences worldwide.

Videos

Speech Topics

Meritocracy and its Discontents

An economic transformation, lasting several centuries, has caused the human capital of free workers to become the single greatest economic asset in the rich nations of the world. This has set in motion a series of epochal moral, social, and political transformations whose full effects are being felt only today. The internal economic inequality that increasingly plagues rich nations is among the most important of these. No thoughtful person can applaud the new economic inequality. But it remains intensely difficult to say just in what ways and for what reasons it is wrong. The nature and causes of economic inequality have been transformed since the middle of the last century, and familiar progressive moral and political arguments against economic inequality no longer suit current conditions. Perhaps most importantly, meritocracy today exacerbates inequality. Meritocratic education, in particular, gives economic inequality a snowball character. Prior inequalities engender new ones, of ever-increasing size. Aristocracy and meritocracy are commonly considered opposed, even opposite, ideals. According to the common view, where aristocracy entrenches fixed accidents of birth, meritocracy promotes equality of opportunity. And where aristocracy allocates advantage according to morally arbitrary heredity, meritocracy allocates advantage to track morally meaningful contributions to the social product, or common good. In fact, the meritocratic achievement that we celebrate today, no less than the aristocratic virtue acclaimed in the ancien régime, is a sham. What is conventionally called merit is actually an ideological conceit, constructed to launder a fundamentally unjust allocation of advantage. Markovits argues that meritocracy is merely aristocracy renovated for a world in which the greatest source of prestige, wealth, and power is not land but skill – the human capital of free workers.

Childhood and Parenting in an Age of Inequality

Economic inequality today, in a fundamental departure from prior eras, is profoundly "meritocratic" -- predominantly caused by the immense wages earned by the intense efforts of highly educated elite workers. Notwithstanding meritocracy's ideological allure, Markovits explains that meritocratic inequality imposes terrible burdens on both the many whom it excludes from social and economic advantage and also the few who gain entry to meritocracy's inner citadel. The unprecedented investments that elite parents today make in educating their children effectively exclude children from non-elite families from the universities and eventually jobs that confer elite incomes and status in today's economic and social order. Meritocracy, initially embraced as the handmaiden of equality of opportunity, has thus become the single greatest obstacle to equality of opportunity in the United States today. At the same time, meritocratic inequality requires the elite--from earliest childhood right through adulthood--to act as asset managers whose portfolios contain their own persons. Meritocracy thus imposes a profound and deeply harmful alienation on the very elite that it appears to favor.

Economic Inequality and Democratic Decline

American Meritocracy was self-consciously designed by Post-World-War-Two leaders determined to open a sclerotic elite to influences from outside of the narrow class of New England Families who had dominated the country for the better part of a century. As Yale President Kingman Brewster said on changing Yale's admissions standards to emphasize academic achievement over family connections: "I do not intend to preside over a finishing school on the Long Island Sound." But although it was conceived democratically, indeed as the handmaiden of equality of opportunity, Markovits explains that meritocracy has become the single greatest obstacle to equality of opportunity in America today. The excess educational investment that a typical rich family makes in a child today--over and above what middle class parents can invest in training their children--is equivalent to a traditional inheritance of between 5 and 10 million dollars. Middle class (much less poor) children simply cannot keep up with the super-trained children of elites in the competition for the best-paying, highest status jobs in an increasingly stratified society. Meritocracy has thus become a powerful vehicle for the dynastic transmission of economic and social privilege. Moreover, meritocratic super-training produces not just economic and social but also political inequality. A short, direct line connects American meritocracy to the many ways in which the rich today dominate both the mass politics of legislation and--less familiarly but even more importantly--elite politics at the intersection of law and their administrative state. Meritocracy and democracy, conceived as allies, have thus become enemies. Indeed, Markovits shows that meritocracy increasingly resembles the aristocracy that it was designed to displace.

Meritocracy, Inequality, and Social Entrepreneurship

In this talk, Markovits explors how conventional wisdom treats science end technology as driven forward by independent and autonomous logics of discovery. In fact, however, the technologies of production invented and deployed in every economy depend, powerfully, on the natural resources with which they are mixed to generate economic output. Among agrarian societies, for example, those located in deserts invent drip irrigation, and those located on flood plains invent rice patty farming. The example illustrates a general truth: technological innovation does not march forward according to inner logic or impersonal necessity but is instead driven by interested innovators, who adapt ideas to economic and social conditions. In modern economies, the greatest economic asset is not land or machinery but rather human capital--the training and skill of free workers. A society's human capital, moreover, is not fixed across time but rather develops, in particular in consequence of the society's practices concerning education and training. The rich nations of the world, and most especially the United States, have in recent decades witnessed an extraordinary investment in training a narrow, super-skilled elite and an unprecedented concentration of human capital in that elite. Exceptional training has reconstituted the elite--traditionally constructed as a leisure class--into a super-ordinate working class. The structure of the economy--including the technologies of production that the economy deploys--has adjusted to the dominant position of this new super-ordinate workforce. The adjustments have imposed deep burdens on the labor force's traditional, mid-skilled core, which is becoming increasingly idle--surplus to economic requirements. At the same time, the mid-skilled labor force remains in place and is, absolutely, more skilled than its predecessors in prior generations (even as it is relatively less skilled than super-ordinate workers). The charisma of elite workers, by transforming the dominant technologies of production to suit super-skills, has thus opened structural opportunities for social entrepreneurship that aims at deploying increasingly under-exploited but still potentially very productive mid-skilled labor.

Can We Make Promises to the People We Love?

In this talk, Markovits explores how when we make a promise, we transfer a moral power to the person to whom we have made it. Before we promise to do something, it is up to us whether or not to do it; but after the promise, it is up to her. Our promise, one might say, establishes its recipient as a moral authority over us, at least with respect to the promised performance. When I make a promise, therefore, I respect the person to whom I have given it: I treat her as entitled to exercise moral authority over me. But this respect also imposes a distance between us: the promise shifts rather than shares authority. An example involving my daughter illustrates the point. When she was six, it became important to her that I promise to do certain things that she wanted--to buy her an ice cream on a weekend afternoon, for example. She specifically wanted a promise and not just a statement of intention--a plan to get the ice cream. And she wanted the promise even though she knew, and would say, that she did not think that the promise increased her chances of getting the ice cream. My daughter wanted the promise because she wanted the authority that the promise conferred. Previously, as a very small child, she had possessed no authority at all: I stood as a benevolent despot ruling over her. But now, as she grew up, she began to assert her independence. My daughter was less interested in the ice cream than in the right to it and, especially, in wielding control over her own rights. The promise enabled her to acquire and assert the control. It was, in effect, her Declaration of Independence. Seeing this changes how we think about other intimate relationships. Take for example marriage. We typically think of marriage as constituted, through wedding vows, by an exchange of promises. But this commonplace in fact disguises the true nature of marriage. A marriage is not a promise but a partnership--it involves not shifted but shared authority. Married people do not owe each other deference but instead embrace a shared commitment to working together to do what is best for the couple. The rejection of the old model of separate spheres and the invention of companionate marriage reinvents the relationship, replacing exchange with sharing. When people nevertheless think of marriage in terms of promises, as they still commonly do, they close themselves of from the real value of partnership and intimacy.

What are Lawyers For?

What are lawyers for? What social purposes do lawyers serve? What functions underwrite the special obligations and entitlements that accompany the lawyer's professional role? Most especially, what functions justify the special dispensations to impose costs on others--indeed to harm innocents--that lawyers enjoy? A commonplace view answers these questions by asserting, often prayerfully, that lawyers and the processes of adjudication that they administer serve truth and justice. The common view is mistaken, however. Instead, Markovits argues, lawyers serve to legitimate power. Lawyers enter conflicts and help to produce agreement about which resolutions to the conflicts to obey in the face of entrenched disagreement about which resolutions to adopt. The lawyer's legitimation of power is therefore not a shallow or even cynical accommodation to the realities of legal practice but rather a profound service that the legal profession provides to the broader social order.

Market Solidarity

Economic markets establish an important and free-standing site of social cohesion. Market solidarity exerts a powerful centripetal force that sustains order agains the centrifugal forces that constantly threaten to tear cosmopolitan societies apart. Although markets appear, on their surface, to invite economic competition--between buyers who seek low prices, for example, and sellers who seek high ones--the deeper logic of market orderings induces collaboration. Prices inaugurate a shared frame of value among traders who disagree about matters of ultimate morality. And exchange teaches commercial virtues--probity, reliability, and good faith--to traders whose first instincts favor ruthlessness and cunning. In spite of its common association with exploitation and injustice, market exchange thus stands alongside politics and the state as a fundamental pillar of order in the modern world.

Related Speakers View all

|

Judge Greg Mathis

Civil Rights Activist, Television Personality

|

|

Zephyr Teachout

Professor at Fordham University School of Law

|

|

Stacey Abrams

Political Leader, Voting Rights Activist & New York ...

|

|

Akhil Amar

Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Y...

|

|

Fawzia Koofi

Former Member of the Afghan Parliament; Internationa...

|

|

Dean Karlan

Behavioral Economist, Social Entrepreneur & Author

|

|

Susan Herman

Constitutional Law Scholar; Former President of the ...

|

|

Rory Stewart

Foreign Affairs & Human Rights Expert

|

|

Nadine Strossen

Professor of Law; President, American Civil Libertie...

|

|

Ben Stein

Political Economist, Commentator, Author & Actor

|

|

Judy Smith

America's Premier Crisis Management Expert; Inspirat...

|

|

Anna Deavere Smith

Award-Winning Actress, Playwright & Social Commentator

|

|

Ralph Nader

Consumer Advocate, Lawyer & Author; Former Independe...

|

|

Julianne Malveaux

Economist, Author & Political Commentator; President...

|

|

Van Jones

CEO of REFORM Alliance, CNN host, Emmy Award-winning...

|

|

Hill Harper

Best-Selling Author, Tech Entrepreneur, Investor, Ph...

|

|

Amy Goodman

Host & Executive Producer, Democracy Now!

|

|

Angela Davis

Feminist, Social Activist, Professor & Writer

|

|

Beau Breslin

Law Professor and Author of "A Constitution for the ...

|

|

Ilan Wurman

Law Professor & Author of "A Debt Against the Living...

|